ENDGAME. We can hope that, rather than being a last gasp, Point Omega is a throat clearing for a major work. |

| Point Omega | by Don DeLillo | Scribner | 128 pages | $24 |

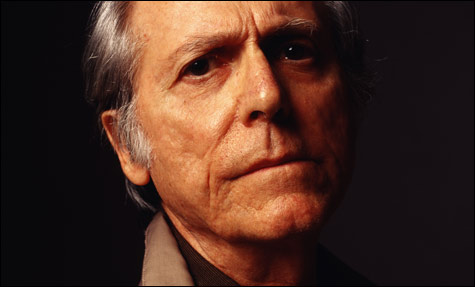

Don DeLillo's novels have been shrinking, like a star collapsing into itself, perhaps, or vapor fading on a glass. From the 800-plus pages of 1997's Underworld they've dwindled down to PointOmega: 117 pages of text, or around 30,000 words — less if the Mamet-like repetitions in dialogue are excluded. Perhaps he's approaching an omega point of his own. "Consciousness is exhausted," one character in the novel declares, citing Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. "Back now to inorganic matter. This is what we want." DeLillo seems tired too, shedding language in search of whatever is left, something like Samuel Beckett's 25-second stage work Breath — an inspiration and exhalation between the cries of birth and death. But instead of a last gasp, Point Omega seems more like a clearing of the throat before beginning another major work.The book's framing narratives, titled "Anonymity" and "Anonymity 2," describe a conceptual piece similar — or is it antithetical? — to Beckett's bagatelle. "24 Hour Psycho," a real installation by the video artist Douglas Gordon that took place at MoMA in 2006, is a screening of Hitchcock's iconic thriller slowed down so that it takes a whole day to unreel. In DeLillo's novel, an unnamed person watches the show with the obsessiveness of Norman Bates and the acuity of a film scholar. He also takes note of the other patrons passing through the gallery, their ephemeral presence more illusory than the near-frozen image on the wall.

At least two of the characters in the "Anonymity" episodes appear in the book's central narrative. Richard Elster, a reclusive 73-year-old pundit and former architect of the War on Terror, invites Jim Finley — an aspiring filmmaker (his only finished work is a compilation of Jerry Lewis doing his telethon) and the first-person narrator of the story — to his desert retreat for a documentary project that sounds like Errol Morris's portrait of Robert McNamara in The Fog of War. Not much filming gets done, however, as the two drink and shoot the bull like a couple of grad students (e.g., discussing Teilhard de Chardin) and Elster reveals himself to be thoroughly detached from the thousands of lives his policies have destroyed. Instead of pondering the morality of his work, he offers aphorisms like "'Consciousness accumulates. It begins to reflect upon itself."

Before things get too solipsistic, Elster's estranged (and not just from him) daughter, Jessica, shows up. Enigmatic and almost autistic, she mildly attracts Finley. She also begins to deconstruct her father's façade of mandarin, nihilist aloofness, seemingly by her very presence — and her absence. Almost makes him human, but not quite.

The other main character is the desert itself, an attenuation of space the way the Psycho project is a prolongation of time. More than the characters, it inspires passages that are reminders that when it comes to a paragraph, a sentence, a word choice, DeLillo is one of the greatest living writers in the English language. "It was too vast," he writes from Finley's point of view, "it was not real, the symmetry of furrows and juts, it crushed me, the heartbreaking beauty of it, the indifference of it, and the longer I stood and looked the more certain I was that we would never have an answer."