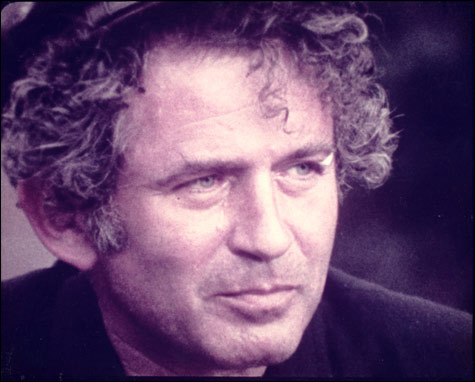

MAIDSTONE: Mailer plays a filmmaker — the heir to Buñuel, Antonioni, and Dreyer — who’s looking to run for president even as he casts a movie that may or may not be pornographic. |

Maybe the trauma of another intractable war has sparked the movies’ recent interest in ’60s headliners: the Beatles in Across the Universe, Dylan in I’m Not There, Vietnam everywhere. This flashback wouldn’t be complete without a look back at the film œuvre of Norman Mailer. If nothing else, a Mailer retrospective provides a window, however distorted and monomaniacal, to a time when writers could be cultural icons as well-known as Paris Hilton is today, a time when movies were analyzed with a passion now reserved for fantasy football. In the ’60s, Norman Mailer was not only a writer, he was a cultural icon. And he aspired to make art movies.

Hence the value of the Harvard Film Archive’s weekend retrospective, “The Cinematic Life of Norman Mailer.” As engaging or entertaining cinema, these celluloid shaggy dogs have their limitations, but then so do the Andy Warhol home movies that were in part their inspiration. Instead, Mailer’s films illustrate the author’s overall theory of film, as described in the section “Film” in his 2003 essay collection, The Spooky Art. The title of the book refers to the art of writing, but it might apply more accurately to film — which, in Mailer’s opinion, is the opposite of writing. Although writing “gets you closer to your soul,” its detachment and the specifying nature of language constricts film’s spontaneity and vital ambiguity. At its best, film can almost re-create external reality itself. At the same time, its power is internal, incantatory, and magical; it is “the physiology of the psyche.” To achieve these ends, it must be improvised, loosely structured, and, it would seem, dominated by an ego like that of Norman Mailer. In short, the ideal auteur combines Warhol’s voyeurism and Kenneth Anger’s shamanism with double shots of bourbon and macho role playing.

Mailer’s first foray into this spooky art fulfilled those ideals, and it did not bode well. After performances of his stage version of The Deer Park in 1968, Mailer and a couple of cronies would drink at a bar and pretend they were mobsters. This is great stuff, they thought, let’s make a movie! So they hired D.A. Pennebaker for $1000, rented a room in a warehouse, filled it with booze and weapons, and let fly.

Or at least Mailer let fly. In WILD 90 (1968; September 23 at 7 pm), he kicks crates, barks at a dog, screams, bellows, sweats, and acts like the belligerent drunk at a party whom everyone tries to placate or avoid. Typecasting, perhaps. The dialogue, what little is audible (Mailer on the film’s sound: “Like it was filtered through a jockstrap”), is scatological, unfunny, and repetitive, like David Mamet on a bad night. Regardless, the film possesses that uncanny quality Mailer valued, the preservation of the past. Even in a home movie, he writes in The Spooky Art, “there is a sense of Time trying to express itself.” He adds that “the years have added magic to what was once moronic.”