This is the first of a two-part series about the changing face of Central Square.In December, Councilor Kenneth E. Reeves presented a report to the Cambridge City Council. "Central, Squared: The Mayor's Red Ribbon Commission on the Delights and Concerns of Central Square" was culled from 16 months of effort by 120 people— landlords, business owners, government officials, and residents — identified as having a large stake in the future of the neighborhood.

The report presents Central Square as a complicated ecosystem of small businesses, social services, and tech giants. "It may be easier to describe what Central Square 'is not' rather than describing what it 'is,' " Reeves writes. "It is difficult to identify one image of Central Square."

Whatever Central Square is, the neighborhood is about to undergo some significant changes. In the coming months, MIT will begin its extension of University Park — the stretch of land between Central Square and the MIT campus — by demolishing the businesses along Mass Ave between Sidney and Landsdowne streets. Soon, All Asia, Thailand Café, and the shuttered Cambridgeport Saloon will be replaced by a 240,000-square-foot research facility. And at 181 Mass Ave, Swiss pharmaceutical giant Novartis — Cambridge's largest corporate employer — will expand its campus with a park and a steel-and-granite tower designed by noted architect Maya Lin.

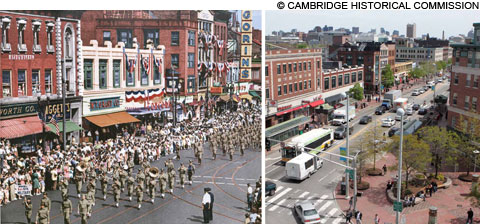

FACE THE CHANGES In this photo from 1946 (left), World War II vets parade down Mass Ave past businesses that (right) are long gone today. |

"Central Square needs a brand," reads a section in the Red Ribbon Commission report. "A brand describes how your key constituents think and feel about what you do. In this case, it answers the questions, 'Why should I spend time and/or money in Central Square?' [and] 'Why does Central Square matter?' "

As tech money continues to saturate Cambridge, Central Square matters more than ever. The neighborhood is the last revenant of Cambridge's less-affluent past. Moreover, it could prove to be the testing ground for any hope of middle-class Cambridge's future.

"The middle class, as elsewhere in Cambridge, is being squeezed out of Central Square," reads the report. If someone earning Central Square's average household income wanted to buy a home, they would fall about $130,000 short. Or, as the Red Ribbon Commission puts it: "Cambridge housing is much more expensive than either lower- or middle-income households can afford."

With an influx of high-paying jobs, and home ownership off-limits to all but the well-to-do, why doesn't Central resemble Harvard or Kendall Square, its wealthy neighbors to the west and east? "We're almost immune from gentrification," Reeves told me over tea at Andala last week. Throughout the neighborhood, 24 organizations provide drug counseling, food, and shelter to people in need. Day and night, the benches of Carl Barron Park stay packed with people with nowhere else to go — 471 "denizens," counted in the 2011 Homeless Census.

"All the social-services industries own their own buildings," says Reeves. "They're not going anywhere; they won't sell, and the populations they serve come to them. As Cambridge gets wealthier, you begin to have people who buy homes in Cambridge from places that are not diverse at all. You hear, 'We don't feel that the benches are for us.' Now, the people who have been on the benches have been on the benches for a long time."