PRIVATE TOUR Urban exploring offers a front-row seat to the city’s inner workings. |

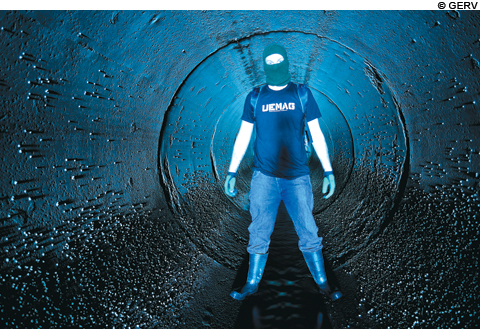

I am crouching somewhere off Portland's peninsula, an inch of water pooled around my winter boots, a dark tunnel of concrete stretching out in front as well as far behind me. To walk deeper into the underground channel requires me to stoop, and so I move, hunched, with the echoes of dripping water and my own footsteps filling the empty space. I'm in the "China Drains," so dubbed by Nicholas Gervin, a/k/a Gerv, who is also my tour guide and trusted companion on this sub-earth adventure.

It's unlikely that anyone who wasn't involved in its construction has ever navigated the inner workings of this particular stormwater drain, and that's part of what appeals to Gerv. Every time this urban explorer discovers new terrain, he feels a little like Vasco da Gama or Neil Armstrong. "Nothing quite beats the feeling of being the first to explore something virgin, never before documented," he writes on his blog, Gerv.com. "It's hard to explain, but the feeling is a bit like Christmas morning as a kid."

Gerv, 31, lives in Portland and is part of an international movement (if you can call localized, diffuse, secretive cells of hobbyists a "movement"): Urban Exploration, the act — and art — of infiltrating underground, abandoned, obscure, or otherwise unseen man-made structures. UrbEx (or "UE") enthusiasts investigate and document everything from drains and bridges to disused asylums and industrial sites to underground tunnel and subway systems. There are active UE scenes in places as diverse as London, Paris, Australia, Russia, Las Vegas, and the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul. Photography is considered by many to be an important component of urban exploration, and the resulting images are often eerie reminders of the layered landscapes we inhabit daily.

Like this one. The China Drains traverse an underground river just below the surface in suburban Portland (Gerv likes to keep his specific locations secret to ensure they don't become overrun). We get to it by traipsing through an empty lot and scrabbling down a rocky embankment. The human-sized concrete pipe comprises one section of the city's 133 miles of storm drain lines (which are in addition to 62 miles of separated sewer and another 133 miles of combined sewer/storm drains that are in the process of being updated). We step into it on a weekday night before Blizzard Nemo hit Maine; had we waited, it probably would have been impassable, filled with melted run-off.

Gerv describes Portland's maze of wastewater drains as a "huge, gigantic, monster underneath the city." Exploring the infrastructure gives him a better appreciation for the operating system as a whole, as well as some historic perspective, a reminder of what goes into building an urban environment.

"I enjoy going places that not many people have been to," he says, "seeing things that have not been seen in years, feeling the forgotten history of our cities and to get away from the norm. There's a whole other world out there that lies just beneath the surface, once your eye are open to it, it's hard to ignore."