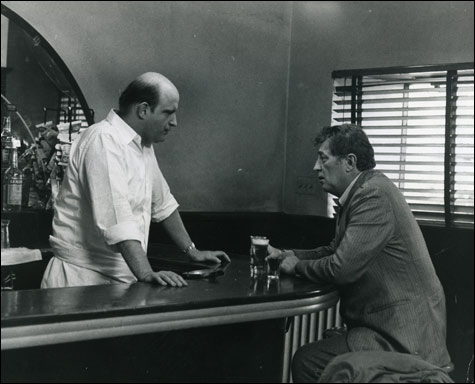

Lehane and Doherty also agree on the book and film that best expresses this point of view. “The Friends of Eddie Coyle,” says Doherty of the Yates film. “You know life is a horrible, meaningless, existential void when your bartender betrays you.”

BAR NONE: The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973) may be the best example of Boston noir, filled with darkly poetic, guilty Irish-Catholics prone to senseless acts of violence.

|

With friends like these

There were noirish movies set in Boston before Yates adapted Higgins’s novel. As Paul Sherman points out in his book Big Screen Boston, some of the first Hollywood films shot here — Mystery Street (1950), Walk East on Beacon! (1952), and Six Bridges to Cross (1955) — are artifacts from the classic period of film noir. But it wasn’t until Robert Mitchum mastered the first decent Boston accent in cinema history and played Higgins’s doomed working-class townie mobster Eddie Coyle that a potential Boston noir genre was born.

And quickly died. Eddie Coyle fared badly at the box office, and any momentum for other Boston-based noir movies halted around the time of William Friedkin’s The Brinks Job (1978). Life imitated art a little too much with Brinks, as the real-life denizens of the Boston-noir world shook down the production. As described in Sherman’s book, the incidents ranged from extortion by the teamsters to gunmen stealing cans of exposed film from the production office, with little recourse from local government offices or agencies.

For years, the pillaging continued and the Boston-based productions dwindled as the city actually ended up on Hollywood’s blacklist. For Nick Paleologos, who took charge of the Massachusetts Film Office in 2007, the ongoing legacy of Hollywood productions looted by Boston locals was his biggest obstacle to restoring the state’s credibility as a location. “I wish I had a nickel for every single time I was confronted in that first year,” he recalls. “Whenever I would do the tax-credit panels in Los Angeles, inevitably, when the Q&A period came, someone would jump up and say, ‘I was in Massachusetts shooting in 1998 or 2001 or ’96 or whatever,’ and everybody had a horror story about being ripped off, and it seemed they all found their way to Teamsters Local 25.”

Then Cambridge natives Matt Damon and Ben Affleck wrote the screenplay for Good Will Hunting (1997) and starred in the film directed by Gus Van Sant. Though not a noir per se, it possessed noir elements, especially with its depiction of the benighted lives and straitened neighborhoods of its South Boston characters. The film proved a critical and commercial hit, receiving nine Oscar nominations and winning two, Best Screenplay for Damon and Affleck and Best Supporting Actor for Robin Williams. (Williams, it must be said, has perhaps the worst Boston accent in any movie. Ever.)

It looked like Boston noir might get another chance. Small, gritty films like Robert Patton-Spruill’s Squeeze (1997), Ted Demme’s Monument Ave. (1998), and John Shea’s Southie (1998) showed promise of sustaining the genre’s life. But not for long.