Maybe, in part, Boston noir faded this time because it was too raw and unironic and seemed naive compared with the hot, hip, self-reflexive neo-noir inspired by Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994). More likely, though, the culprit was a familiar one. Chuck Hogan, in his book Prince of Thieves, sums it up in a deft touch of irony that I hope Affleck keeps in The Town. He writes about one of the bank robbers:

Gloansy, in his legit life as a sometime union driver for local movie productions, was always nicking stuff off sets. Props, cables, snacks — anything he could eat or move. Off an Alec Baldwin movie called Malice he had taken a makeup kit . . .

The gang uses this kit to disguise themselves to pull off one of their biggest heists — knocking over the Braintree 10 Cinema after the blockbuster opening weekend of Twister. No better anecdote sums up the Boston-filmmaking scene of the era; the off-screen criminals were exploiting the ones on screen rather than the other way around.

Lehane, who had ventured into making a feature around this time (his film turned out to be unintentionally and uncannily similar to Good Will Hunting and was never released), has bad memories of this period. “In the ’90s, when I was in the independent-film scene in Boston — I can’t tell you the horror stories about that,” he says of the rip-offs and abuses, perhaps fearing a visit from the teamsters. “I saw some really terrifying things, and it ran everybody out of town.”

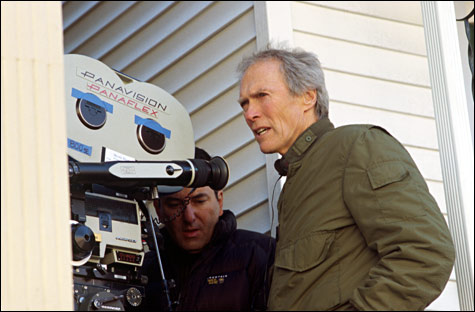

But, as he has done onscreen in so many of his movies, Clint Eastwood rode to the rescue.

“Clint came in and kind of worked a deal and said, you know, ‘If you stick me up, don’t stick me up too heavily,’ ” recalls Lehane about the making of Mystic River. “It worked, and it brought a lot of good things to the city.”

A GENRE REBORN: Clint Eastwood’s adaptation of Mystic River (2003) captured two Oscars, and the attention of studios, paving the way for the state’s filmmaking tax breaks. |

Back from the Brinks

Did Clint tame the bad guys? Or did they merely become extinct? Like many noirs, the Boston films exude a nostalgia for an illusory lost world, a prelapsarian paradise where neighborhoods and families reigned supreme, where men were men, and nobility, loyalty, and love prevailed.

Those who happened to live in those times, who recall instead the viciousness, ignorance, grief, and poverty, might think, “good riddance.” They welcome the gentrification, homogenization, and soaring property values; the condos supplanting tenements; the Starbucks and fern bars replacing the local bucket-of-blood barrooms and greasy-spoon diners; the extortionate rents driving away those who didn’t cash in.

The new noirs, though, celebrate an idyllic yesterday that never was, glossing over what essentially was another round in America’s ongoing conflict. And in this case, as usual, the haves were the winners, and the losers got to have films made about them.

“There’s a funeral going on for that world,” says Lehane. “The world that you see in The Departed; the world that you see in Mystic River; the world that you saw in Monument Ave.; the sort of European ethnic neighborhood, that sort of clannishness. It’s departing, and I think there’s a bit of a funeral being held and it’s showing up in those movies. But you know, there’s a reason these floors get swept.”